I decided also to study books of the Protestant Apocrypha, and so this week I've been studying 1 and 2 Maccabees, with a quick look at 3 and 4.

1 Maccabees is a deuterocanonical book in the Roman Catholic (the term for Easter Orthodox Bibles is Anagignoskomena). 1 Maccabees is found in the Greek Septuagint but not in the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible, nor in Protestant Old Testaments. Canonical or not, it is an important account of this period of Second Temple Judaism, the decades of Judean independence prior to the Roman occupation, and is the source for the minor Jewish festival Hanukkah. (Here is a good Catholic site about the book. Some Catholic Bibles place 1 and 2 Maccabees after Esther, while other Catholic Bibles place the books at the end, after Malachi.)

1 Maccabees covers about forty years, 174 to 134 BCE. It might be good to see a biblical chronology again:

- Patriarchs: about 1800-1500 BCE (Genesis)

- Exodus, Wilderness, and Conquest: about 1500-1200s BCE (Exodus-Joshua)

- Period of the Judges: 1200s-1000 BCE (Judges)

- The monarchy (Saul, David, Solomon): 1000-922 BCE (1 and 2 Samuel, 1 Kings 1-11, 1 Chronicles, 2 Chronicles 1-9)

- Divided monarchy: 922-722 BCE (1 Kings 12-17, and also Isaiah, Hosea, Amos, and Micah)

- Kingdom of Judah: 722-586 BCE (2 Kings 18-25, 2 Chronicles 10-36, and also Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Joel, Obadiah, Jonah, Nahum, and Habakkuk)

- Exile: 586-539 BCE (Lamentations, Psalm 139, et al.)

_ Judah under Persian rule: 539-332 BCE (Ezra-Nehemiah covers about the years 539-432 BCE, while Esther is set during the reign of Xerxes I, who reigned 486-465 BCE. Also, the prophets Second Isaiah, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi)

- Judah during the Hellenistic rule: 332-165 BCE (3 Maccabees, Daniel)

- The Maccabean/Hasmonean period: 165-63 BCE (1, 2, and 4 Maccabees)

- Judea under Roman rule: 63 BCE-135 CE (during which time we have the life of Jesus, the first two generations of the church (30-120 CE), the writings of the New Testament (about 50-100 CE), and the beginnings of Rabbinic Judaism, after the Temple's destruction in 70 CE).

Our upcoming scriptures, the Prophets, date from the end of the Northern Kingdom in the 700s BCE (Isaiah) down to the 400s BCE of the Persian period (Malachi), while parts of Daniel probably date from the Maccabean period. So the Jewish Bible and Protestant Old Testament end historically with the 400s of the Persian period, with apocalyptic writings in Daniel dating from the Maccabean era, while the churches with deuterocanonical books carry the Old Testament history solidly into the 100s BCE.

Back to 1 Maccabees: At the time, Judah (by now called Judea) is ruled by the Seleucid Empire, the Greek domination that followed Alexander the Great’s empire. Greek culture was influential for Judaism, including the translation of the Bible into Greek; but Greek disrespect for Jewish practices lead to the Jew’s revolt against the Greeks, which is the subject of the book. 1 Macc. 1:1-9:22 concerns the rule of Mattathias, aka Judah the Maccabee (the word means “hammer”), aka Judas Maccabeus. 1 Maccabees 9:23-12:53 focuses on the rule of Judah's successor Jonathan, and chapters 13-16 concern the rule of Simon.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes, one of the villains of Jewish history, was the Seleucid emperor who launched a bloody attack on Jerusalem, taxes the people, forbids Jewish practices, and then desecrates the Jewish temple by establishing pagan rituals there, including the slaughter of non-kosher animals.

Judas leads the people in ultimately successful campaigns against the Greeks, though at a high cost in casualties. When the temple is retaken and reconsecrated, Judas and his brothers and the whole assembly established a festival of the 25th day of Chislev (Hanukkah) to commemorate the dedication (1 Macc. 4:59).

(Here are good source concerning Hanukkah: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/hannukah and http://www.jewfaq.org/holiday7.htm. I was surprised to learn that the famous story of the lamp--which burned for eight days with only one day of oil--is from the Talmud [Shabbat 21b] rather than Maccabees: http://cojs.org/babylonian_talmud_shabbat_21b-_the_significance_of_hanukkah/ )

|

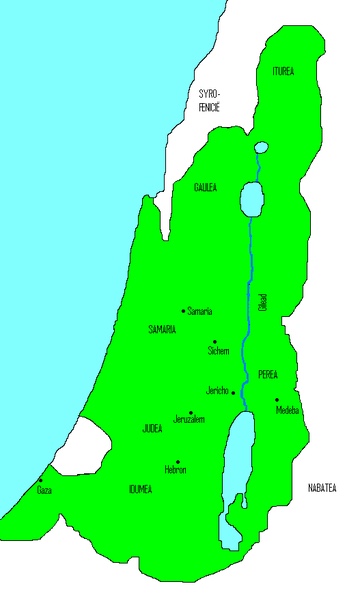

| Hasmonean Kingdom at its height. From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hasmonean_dynasty |

(Here is a famous song from Handel's oratorio Judas Maccabeus.)

2 Maccabees does not, as you might think, continue the history. It begins with letters written by Palestinian Jews to Egyptian Jews, and then becomes an abridgment of a now-lost history by Jason of Cyrene about the Maccabean revolt under the leadership of Judas Maccabeus. The book also includes the stories of Jewish martyres Eleazar, seven brothers, and their mother, under Antiochus’ reign. As this site indicates, it is a very laudatory book toward Judas and Jewish heroism; it includes information not found in 1 Maccabees, and it references Esther. 2 Maccabees is also part of the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox canon.

Here is a good Jewish site about the book. That author writes: “One important fact to be noted is the writer's belief in the bodily resurrection of the dead (see vii. 9, 11, 14, 36; xiv. 16; and especially xii. 43-45). This, together with his attitude toward the priesthood as shown in his lifting the veil which I Maccabees had drawn over Jason and Menelaus, led [scholars] Bertholdt and Geiger to regard the author as a Pharisee and the work as a Pharisaic party document. This much, at least, is true—the writer's sympathies were with the Pharisees.” (Here is another good site.) Because of the doctrine of the resurrection of the dead, 2 Maccabees also provides an important theological bridge to the New Testament period.

In fact, 2 Maccabees may be alluded to in the New Testament, especially Hebrews 11:35, "Others were tortured, refusing to accept release, in order to obtain a better resurrection" (NRSV). This does not fit any Old Testament story but does fit the story of the seven brothers in 2 Maccabees 7, a fact that this author uses to defend the canonicity of the deuterocanonical books.

3 Maccabees is found in the Eastern Orthodox canon but not in the Jewish, Protestant, and Roman Catholic canons. 3 Maccabees is not set during the Maccabean age at all but shares with those books the wonderful intervention of God on behalf of God’s people. In this book, Egyptian Jews are persecuted by another Seleucid ruler, Ptolemy IV Philopator, who reigned in 221-203 BCE). Again, Jews are hated because they don’t worship foreign gods, in this case Dionysus, but the story includes a different kind of Gentile persecution: letting inebriated elephants trample imprisoned Jews to death! Ptolemy’s inconsistency, however, and also the intervention of two angels, allow the Jews to be spared. (Here is a good site.)

4 Maccabees is not canonical in any Jewish tradition, nor in any Christian canon except the Georgian Orthodox Church. Another important text for understanding the Second Temple period, the book is a homily to encourage Hellenistic Jews to stay devoted to Torah (18:1) and to hold courageously to “devout reason” that is "sovereign over the emotions" (e.g., 16:1). A sizable portion of the book describes (in gruesome detail) story of 2 Maccabees 6:18-7:42: the martrydom of Eleazer, and the seven brothers and their mother. Stories of martyrs are important in many religions, to help build courage to believers in times of trial. In Judaism, martyrdom is one example of Kiddush HaShem, "sanctification of the name" (of God) through holiness and witness.

Interestingly, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church's Bible contains three books--1, 2, and 3 Meqabyan--not found in any other Christian canon, which are different in content from the Maccabees books. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meqabyan

Enjoyed reading this Paul...I've never read Maccabees, but have been curious about it's content. Thank you for this insight.

ReplyDeleteThanks, cuz! I don't remember ever reading it, either, even in seminary, so it was interesting to study!

Delete