This calendar year (and probably into Lent 2018), I’m reading through the Bible and taking informal notes on the readings. Since we so often read verses and passages of the Bible without appreciating context, I’m especially focusing on the overall narrative and connections among passages.

This calendar year (and probably into Lent 2018), I’m reading through the Bible and taking informal notes on the readings. Since we so often read verses and passages of the Bible without appreciating context, I’m especially focusing on the overall narrative and connections among passages.Here are a few more thoughts and notes about Jeremiah.

As I write on one of my other blogs: When I was a young person, in Sunday school in our small town church, I pictured the long biblical text in an unusual way: as if it was a landscape for exploring. My dad was a truck driver who hauled gasoline and fuel oil, and so images of travel and “the open road” come naturally to me. (The Bible contains 66 books, and Dad regularly drove Route 66 in Illinois … how providential!) Perhaps I was also inspired by the well-used maps at my church of Bible lands, maps which seemed as interesting as the folded maps, free at filling stations, in the glove compartment of our family car. I imagined the Bible as a large area, not of Palestine, but of sections of landscape, like states, laid out for more or less eastbound travel—even if you began with the New Testament but then backtracked to the Old, as I’ll do in a moment. (When I read my favorite translation of the Torah with its Hebrew text, I begin to imagine the right-to-left text as westbound.)

At the Bible’s beginning, the “scenery” is interesting from Genesis through about 2/3 of the way through Exodus. A few places become tedious—the genealogies, for instance—but the reading moves along, peaking in cinema-ready excitement with the Red Sea crossing, the Ten Commandments, and the Golden Calf. The reading slows as you journey through Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. But you’ve encountered some of the Bible’s high points: the Creation, the Flood, Abraham’s call, Egyptian slavery, the Exodus, and the revelation at Sinai.

You continue on a varied landscape though the historical books: some good parts, some dry. Judges and 1 and 2 Samuel contain violence and intrigue. Beyond, as you pass through the books of Kings and Chronicles, the “travel” becomes tougher again. Do I really need to know all those kings—who sinned and how badly—and lists of names, in order to be saved, to love the Lord?

But in this landscape, too, we find high points: the conquest of the Land, the establishment of the monarchy and kingdom (with David and Solomon as the key figures), the destruction of Jerusalem, the Exile, and the Restoration. Understanding the Bible requires some grasp of these events.

After the historical books, the journey becomes more interesting again. Among the writings, the Psalms alone are worth many revisits; Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Songs, too. Then you embark on journey through the prophets. The prophets contain fascinating material, but without the narrative structure of the historical books, and without a clear chronology, the prophets’ writings can seem scattered and hard to grasp. A person can lose her bearings there.

You reach the New Testament, which—again, in my young imagination—I pictured as a wonderful landscape that gradually narrows. That’s because the New Testament books tend to become shorter and shorter. Little-bitty 2 John, 3 John, and Jude have only one chapter each, compared to Matthew’s 28. It was as if God was focusing your spiritual travels toward the end times and salvation, the subject of the longer, finally book of Revelation.

I think of some of these longer biblical books in "landscape" imagery. Isaiah, with its several oracles about Isaiah, Judah, and the nations, begins really to feel like a "map" of poetry and images, until we get to chapters 40-66, which I imagine in terms of a lovely and sunny, blue sky. (See, for instance, 60:19-21!)

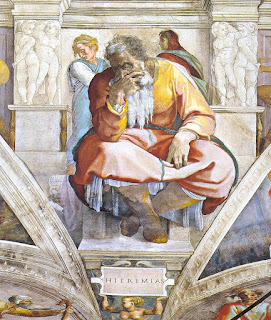

Jeremiah "feels" like a more rugged landscape, with cisterns and broken pots, yokes, cities destroyed or promised to be destroyed, bitter wailing, finally a scroll weighed by a stone and cast into the sea.

In his book Biblical Literacy, Rabbi Telushkin calls Jeremiah "the loneliest man of faith." Like Moses and David, we learn a lot from the Bible about his desolate moments, but also, he "is the only character in the Bible who is denied a family. Early in his career, God decrees that Jeremiah is to live alone: 'the word of the Lord came to me. You are not to marry and not to have sons and daughters in this place' (16:1-2)." This is because of the violence to come (Biblical Literacy, pp. 293-294). Tragically, Jeremiah also had to see his predictions come true (p. 295).

******

Among the well-known passages of this prophet is Jeremiah 20:7-18, a text that I first discovered in div school. Here is the NRSV:

O Lord, you have enticed me,

and I was enticed;

you have overpowered me,

and you have prevailed.

I have become a laughing-stock all day long;

everyone mocks me.

For whenever I speak, I must cry out,

I must shout, ‘Violence and destruction!’

For the word of the Lord has become for me

a reproach and derision all day long.

If I say, ‘I will not mention him,

or speak any more in his name’,

then within me there is something like a burning fire

shut up in my bones;

I am weary with holding it in,

and I cannot.

For I hear many whispering:

‘Terror is all around!

Denounce him! Let us denounce him!’

All my close friends

are watching for me to stumble.

‘Perhaps he can be enticed,

and we can prevail against him,

and take our revenge on him.’

But the Lord is with me like a dread warrior;

therefore my persecutors will stumble,

and they will not prevail.

They will be greatly shamed,

for they will not succeed.

Their eternal dishonour

will never be forgotten.

O Lord of hosts, you test the righteous,

you see the heart and the mind;

let me see your retribution upon them,

for to you I have committed my cause.

Sing to the Lord;

praise the Lord!

For he has delivered the life of the needy

from the hands of evildoers.

Cursed be the day

on which I was born!

The day when my mother bore me,

let it not be blessed!

Cursed be the man

who brought the news to my father, saying,

‘A child is born to you, a son’,

making him very glad.

Let that man be like the cities

that the Lord overthrew without pity;

let him hear a cry in the morning

and an alarm at noon,

because he did not kill me in the womb;

so my mother would have been my grave,

and her womb for ever great.

Why did I come forth from the womb

to see toil and sorrow,

and spend my days in shame?

Like some of the psalms, this passage mixes despair directed at God, with praise at God’s ability to rescue and prevail. Unfortunately, Jeremiah also feels that God has prevailed over him, in gifting him as a prophet and thus giving him over to a life of misery, rejection, and shame.

Verse 7 is particularly strong language directed at God. Years ago I wrote in my margin that the Hebrew word pata (deceive or entice) also means “seduce,” while the word yakol (prevail) has a strong sexual connotation. The sense is that God seduced and then raped Jeremiah.

When we discussed this passage in div school, our interests were in a feminist reading (1)---the language of sexual violence that we find here and elsewhere in some of the prophets, particularly Ezekiel---and also a pastoral reading---what does it mean to be called to ministry but then feel deceived by God?

Look at verses 14-18. To use a crude expression, Jeremiah declares, in effect, “F my life.” He wishes he’d never been born. Loathing of himself and fury at God are two sides of the same experience. And don't forget---these are words of the Bible, God's word for us!

Jeremiah expresses anger and despair both at God and toward his own sense of self-worth. And yet he remains true to his calling. Part of his despair is, indeed, that he is committed to this life of faith and will not deviate from it, even though, in his perception, God has treated him in the worst possible way.

I can't fail to call attention to topics of date-rape and “rape culture.” I found the following blog helpful: the author and some commenters discuss issues of gender, gendered emotional response, and sexual violence that this passage implies: http://theroundearthsimaginedcorners.blogspot.com/2012/06/god-and-images-of-rape-in-jeremiah.html

*****

Some of our memorable New Testament imagery comes from Jeremiah, for instance, 31:31-34.

The days are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah. It will not be like the covenant that I made with their ancestors when I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt—a covenant that they broke, though I was their husband, says the Lord. But this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those days, says the Lord: I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people. No longer shall they teach one another, or say to each other, ‘Know the Lord’, for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, says the Lord; for I will forgive their iniquity, and remember their sin no more.

"New Testament" is a synonym for "new covenant"--so the very name of the Christian portion of the Bible derives from Jeremiah.

I discuss this passage in my book Walking with Jesus through the Old Testament (pp. 78-80). There I quote Walter Brueggemann, "The ground of the new covenant is rigorous demand. The covenant requires that Israel undertake complete loyalty to God in a social context where attractive alternatives exist" ("The Book of Exodus," The New Interpreter's Bible, vol. 1 (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994), 951).

We also have a lovely passage from 23:5:

The days are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will raise up for David a righteous Branch, and he shall reign as king and deal wisely, and shall execute justice and righteousness in the land.

The sorrow of Rachel, evoked in 31:15-17, is used by Matthew in his narrative of the massacre of the innocent (2:13-19).

Jeremiah's sermon about the Temple, 7:8-15, is cited by Jesus as he (Jesus attacks the money changers at the Temple. As I discuss in my book (p. 117), the reference to "a den of robbers" has less to do with the honesty of the traders, than with Jeremiah's original metaphor: Jeremiah's contemporaries believed God would protect them as long as they worshiped at the Temple, but Jeremiah likened that idea to a group of thieves who thought they were safely in hiding but were not.

*****

A verse from Jeremiah cut me to the heart when I first learned it, during a life changing divinity school class taught by B. Davie Napier. As I write this, we are in a national crisis situation concerning the well-being of non-documented immigrants and their children.

He judged the cause of the poor and needy; then it was well. Is not this to know me? says the Lord (Jer. 22:16).

Wow. If we love God but are uncaring toward the needy and begrudge them help, we’re fooling ourselves. We not only fail in loving God, we don’t even know God! King Josiah, though, knew God, according to Jeremiah. This verse dovetails well with Micah 6:6-8, and 1 John 4:20b, as well as Matthew 25:31-46 and James 2:14-17. So why don’t more of us step up and care for the poor, with such a plain scriptural teaching? Even the straightforward verse John 3:16 implies helpfulness to the needy, for if you believe in Christ as John 3:16 instructs, you respond to “the least of these” (Matt. 25:40).

The pleasures of Bible reading often return me to this theme, because if you want to know a set of “characters” that pervades the scripture, it is the people variously and generally called the poor, the widow and orphan, the needy, the oppressed, the alien, and the stranger. With my Topical Bible and other sources, I’ve “collected” a very small selection of the total: Exodus 22:22; Leviticus 19:10, 15; Deuteronomy 10:19, 14:28-29; 15:7-8; Job 29:12; Psalms 14:6, 82:3-4; Proverbs 14:21, 14:31, 17:5; Isaiah 58:6-7; Ezekiel 16:49; Matthew 19:21, 25:35; Luke 4:18, 12:33, Acts 9:36, 10:4; Galatians 2:10; James 1:27; 1 John 3:17-18. My book Walking with Jesus through the Old Testament has a lesson on this subject.

I’ve been inspired by Jewish friends and their concern for tzedakah, “righteousness” or “charity,” which has replaced the biblical sacrifices as a response to God. Many Jews are quick to “give back to the community” and to take the side of the needy (not necessarily the Jewish needy!) in their donations and political convictions.On the other hand I’ve known Christians, including some pastors, who love the Lord to the point of becoming teary-eyed about God’s blessings, and yet those same Christians express a harsh political outlook toward the poor. How many times have I heard Christians speak disdainfully of the poor, as if all poor people were lazy, out to cheat the system. I feel shame when I think of my own hard-heartedness toward the poor: for instance, a time when I became silently impatient in a grocery line as a young couple up ahead paid for their groceries with food stamps.

I believe there are many ways to know God, because we all have different personalities, talents, abilities, cultural backgrounds, and experiences. The variety of the Bible’s theological perspectives attests to the importance of variety among people’s religious walks. But this way to God haunts me and always has, from which my conscience can never escape: the trumpet call of Micah 6:8, that rhetorical question of Jeremiah 22:16, the clear words of Matthew 25:40.

(This last section is from another blog of mine, theloveofbiblestudy.com, chapter 1).

A verse from Jeremiah cut me to the heart when I first learned it, during a life changing divinity school class taught by B. Davie Napier. As I write this, we are in a national crisis situation concerning the well-being of non-documented immigrants and their children.

He judged the cause of the poor and needy; then it was well. Is not this to know me? says the Lord (Jer. 22:16).

Wow. If we love God but are uncaring toward the needy and begrudge them help, we’re fooling ourselves. We not only fail in loving God, we don’t even know God! King Josiah, though, knew God, according to Jeremiah. This verse dovetails well with Micah 6:6-8, and 1 John 4:20b, as well as Matthew 25:31-46 and James 2:14-17. So why don’t more of us step up and care for the poor, with such a plain scriptural teaching? Even the straightforward verse John 3:16 implies helpfulness to the needy, for if you believe in Christ as John 3:16 instructs, you respond to “the least of these” (Matt. 25:40).

The pleasures of Bible reading often return me to this theme, because if you want to know a set of “characters” that pervades the scripture, it is the people variously and generally called the poor, the widow and orphan, the needy, the oppressed, the alien, and the stranger. With my Topical Bible and other sources, I’ve “collected” a very small selection of the total: Exodus 22:22; Leviticus 19:10, 15; Deuteronomy 10:19, 14:28-29; 15:7-8; Job 29:12; Psalms 14:6, 82:3-4; Proverbs 14:21, 14:31, 17:5; Isaiah 58:6-7; Ezekiel 16:49; Matthew 19:21, 25:35; Luke 4:18, 12:33, Acts 9:36, 10:4; Galatians 2:10; James 1:27; 1 John 3:17-18. My book Walking with Jesus through the Old Testament has a lesson on this subject.

I’ve been inspired by Jewish friends and their concern for tzedakah, “righteousness” or “charity,” which has replaced the biblical sacrifices as a response to God. Many Jews are quick to “give back to the community” and to take the side of the needy (not necessarily the Jewish needy!) in their donations and political convictions.On the other hand I’ve known Christians, including some pastors, who love the Lord to the point of becoming teary-eyed about God’s blessings, and yet those same Christians express a harsh political outlook toward the poor. How many times have I heard Christians speak disdainfully of the poor, as if all poor people were lazy, out to cheat the system. I feel shame when I think of my own hard-heartedness toward the poor: for instance, a time when I became silently impatient in a grocery line as a young couple up ahead paid for their groceries with food stamps.

I believe there are many ways to know God, because we all have different personalities, talents, abilities, cultural backgrounds, and experiences. The variety of the Bible’s theological perspectives attests to the importance of variety among people’s religious walks. But this way to God haunts me and always has, from which my conscience can never escape: the trumpet call of Micah 6:8, that rhetorical question of Jeremiah 22:16, the clear words of Matthew 25:40.

(This last section is from another blog of mine, theloveofbiblestudy.com, chapter 1).

No comments:

Post a Comment